In 1977 I was a precocious seven-year-old with an impressive record collection (built on the 13-albums-for-one-cent deal from Columbia House) and a crystal AM radio. Strange things happen when your brain matures before your body. You feel like an adult before your height or peer-group membership entitle you to adult status. You can attract the hostility of those peers and in response become cool and contemptuous, traits you’ll later need to outgrow. But the upside is being able to pursue adult interests with the freshness and energy of a kid. Whenever I got tired of baseball, tag, war, wrestling, and so on, I would retreat to my parents’ dining room and plant myself under the table with the crystal radio and its single earpiece. It was there that I first heard Steely Dan.

The song was “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.” I could hear the lyrics clearly, but the meaning was obscure. Who was Rikki? What was important about the number? The singer didn’t really sound like a singer, either. He seemed to be sneering more than singing. Moreover, he sounded completely and utterly knowing. Where had he acquired this perfect knowledge? How had he acquired this attitude? I was intensely curious. Alas, I had burned through the entire 13-album deal and lacked the cash to fulfill my record-buying obligations. (To this day, I wonder if deadbeat seven-year-olds ended up bankrupting Columbia House.) My curiosity about this Dan guy would have to wait.

I didn’t really start listening to Steely Dan in earnest until I was a junior in high school. That year my mother put my brother and I on a bus to Port Authority and the filth and chaos of pre-Giuliani New York. On the bus a derelict man with an eye patch and a motorized larynx told us to “Shut the hell up,” which we did. When we arrived at the station we were greeted by my cousin’s husband, a slight guy with zero athletic presence but plenty of New York attitude. We passed through a narrow hallway where a busker was playing a marimba. An aggressive panhandler asked us for money. “Fuck off,” snarled our guide. That was our brief tutorial in the attitude. Back at my cousin’s apartment, we ate Jamaican takeout and listened to Aja. The associations of urban chaos, third-world cuisine, and the music all stuck, and in our minds the Dan became the official soundtrack of the New York visit. “That New York smartass music,” my brother called it.

There were other times and other associations. My jazz piano teacher, a sideman for Sammy Davis Jr., never mentioned the Dan, but as I learned about them he began to make a lot more sense to me. His den where I took lessons smelled like pipe smoke and was littered with books by Abbie Hoffman and William S. Burroughs. These references became part of my mental furniture and were coterminous with the band’s worldview. Then there was the retail job I had during my college summers in a print shop. “Peg” and “Josie” had made it onto the corporate muzak playlist, and I heard each in the store two or three times a day. They were the only songs on the CD I never got tired of. I also enjoyed the irony of hearing the slick and sharp-witted songs in the airheaded environment of a suburban mall. Steely Dan consistently pitched over everyone’s heads, and instead of saying they didn’t care what anyone thought about them, truly and utterly didn’t.

In late September 2001 I was living in Brooklyn and still shell-shocked from 9/11, a day I spent running around and hiding in Lower Manhattan. When I finally felt well enough to leave my apartment, I wandered into a bookstore in Brooklyn Heights and picked up Brian Sweet’s Reelin’ in the Years. For the first time I actually started learning about the band, and the more I read, the more intrigued I became. I loved the way they had used studio musicians, eschewed touring, and achieved fame on their own terms. I liked their cryptic, oblique tone in interviews and their coldness towards media figures who expected them to curry favor. I got deeper and deeper into the band’s catalog, especially the amazing run from Can’t Buy A Thrill (1972) to Gaucho (1980).

Many people do not like Steely Dan. A lot of women find them creepy and misogynistic—a charge that may have some merit. Others find the music too bland or smooth. When I saw George Carlin perform a few years before he died, he made a special point of mocking “the kind of people who listen to Steely Dan.” I could have been offended, but instead was just surprised — surprised that he’d missed the irony and humor that actually were on a par with his own. Somehow he had mistaken the muzak for the music. Such is the price of pitching over people’s heads, I suppose.

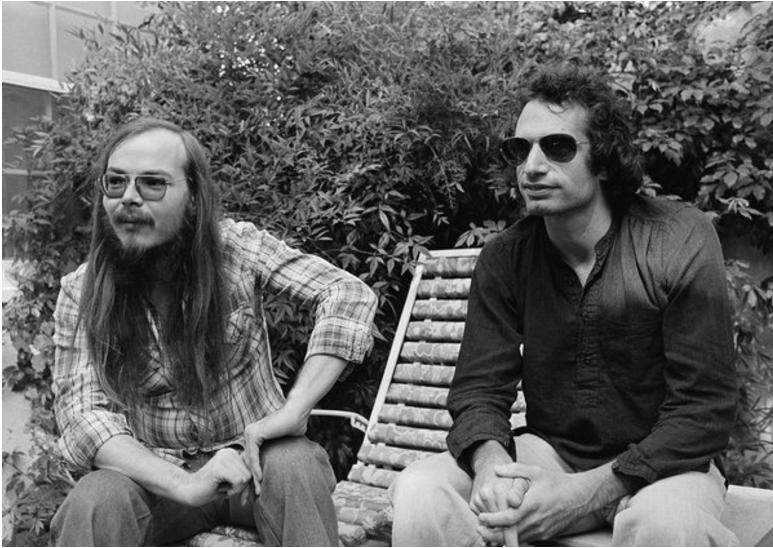

When I heard this week that Walter Becker had passed away I felt empty and sad. There are a limited number of hyper-literate, hyper-ironic Northeastern smartasses in this world, and when one dies, a part of me dies with him. I was at least glad I had seen the band live in 2015. Donald Fagen is still with us, thankfully. He has pledged to do all he can to keep the band’s music alive as long as he lives. It’s a much smaller gesture on my part, but as a fan and a musician myself, I will do the same.